The History of the Passion

The Passion of Jesus Christ lies at the very centre of the Christian faith and has inspired a great number of musical works dating from the earliest years of Christianity until the present day. In the bible, the various descriptions of the final episode in Christ’s mortal life on Earth are found in the four gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, which constitute the fundamental part of the New Testament. Many modern scholars think that the body of text which makes up the fourth canonical gospel was not in fact written by John the apostle, and disciple of Christ, at all, but is a collection of eye-witness events assembled and written anonymously by more than one person. It was written in Greek, and contains more direct claims to eye-witness events than any of the other gospels. It shows evidence of having been written in three distinct layers, at three different times, reaching its current and final form at around 100 AD. It is highly probable that it was composed, and later twice edited / supplemented, by members of a Johannine community – disciples or followers of John, the origins of which can be traced back to John. The non-canonical Dead Sea Scrolls suggest an early Jewish origin. There is a significant amount of duplication between the gospel and the scrolls. The gospel begins with a prologue which sets forth the doctrine of the incarnation of the eternal word, and then recounts events from Christ’s life, from his baptism as a young adult until the three appearances which he made to his disciples after the resurrection. There is no mention made of either the nativity or the ascension.

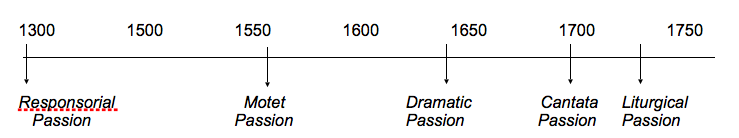

From the Middle Ages it was common practice to intone the words of the Passion story on Passion Sunday (the Sunday before Palm Sunday) and again on Good Friday in a plainsong chant known as a choraliter. The Lutheran church quickly adopted this Catholic tradition and, as the art of composition developed, this soon developed into a polyphonic form which was to pass through a number of stages.

Responsorial Passion |

Biblical text intoned to Gregorian chant in Latin as an act of worship. |

|

Motet Passion |

The entire evangelical text is set polyphonically, and by now in the vernacular, as the effects of the Protestant reformation take hold (e.g. the Passion by Roland de Lassus). |

|

Dramatic Passion |

The recitative does not follow the biblical text, but is a free prosaic invention inspired by it, and based on a “sacred libretto” (e.g. the Passion by Heinrich Schütz). |

|

Cantata Passion |

The performance is separated from a liturgical act of worship and performed in the context of an oratorio. Words are not biblical but are also written as a libretto (e.g. the Passion by Reinhard Keiser). |

|

Liturgical Passion |

Performed as a liturgical celebration in two parts, either side of a lengthy sermon, the biblical text restored, but interspersed and interpolated with reflective arias and chorales for the congregation to sing. This is the structure used by Bach. |

By the time Bach arrived in Leipzig it was customary for there to be a performance of the St John Passion on Good Friday and one of the St Matthew Passion on Palm Sunday, both in St Nicholas’s – the Passion being a prominent feature of Protestant religious observance, although this tradition had only been instituted in 1721, and so it was still quite a new concept. Bach began the tradition of an annual Passion on Good Friday alternating between St Thomas’s and St Nicholas’s. This practice was by no means peculiar to Leipzig. In Italy the famous opera librettist and playwright Pietro Metastasio (1698-1792), who supplied opera libretti to Handel, Gluck, Haydn and Mozart amongst others, had started to compose texts for musical settings of the Passion.